¨Too soon we get old and too late we get smart¨, my uncle Bob used to tell me as he bounced me on his knee.

He was right.

Living in Nicaragua is an exercise in patience now. Staying in is key as it’s not a good idea to gallivant around. There are barricades on the Pan-American highway near where I live in Diriamba and many other places.

So I’m hunkered down, reading some texts I used to assign in my college classes, photographing my orchids, cooking my favorite foods, harvesting my avocados, watching the national dialogue, and wondering what to do next.

A quick guide to the Nicaraguan National Dialogue.https://t.co/q9obKFgotE#nicaragua #sosnicaragua

— CentralAmericaLiving (@VidaAmerica) May 18, 2018

This latest political hiccup was a surprise.

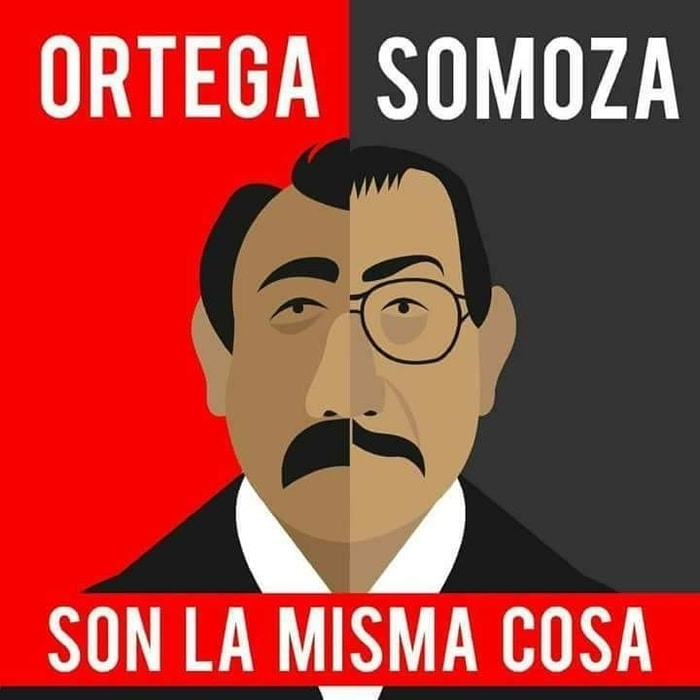

I lived in Nicaragua in the halcyon days of Somoza Debayle and returned in 1987, the bloodiest year of the Contra War.

Since 1990, when Violeta Chamorro won the presidency, there has been nothing like this.

I may not be the most informed person here, but I’m not uninformed. I speak the language, including slang and cuss words, and keep up with things.

This week I meant to go poking around El Realejo, one of the premiere Spanish colonial shipbuilding centers in Central America. I canceled the trip due to the continued violence around Leon and Chinandega.

Actually, living in Nicaragua is pretty enjoyable – or has been, at least.

I worked at the American School and later at an American university for twenty years, retired, and worked on a large archaeological project.

During the Contra War, I wandered the northern mountains where things were not too hot. I found some pretty good gold panning, did some horse packing, and began collecting Nicaragua’s orchids.

I got hired by Izvestia, and later the Los Angeles Times, to cover stories and take journalists – most from the Eastern block and interested in the local booze and um, “companionship” – into the mountains to get a whiff of the war.

Op-Ed: Nicaragua’s democracy is falling apart https://t.co/cpgFGeIKzZ (via @latimesopinion) pic.twitter.com/cRl83QcQAf

— Los Angeles Times (@latimes) April 27, 2018

They paid me well paid for my time and I took relatively few risks.

I also worked awhile on the Miskito Coast of Nicaragua.

My business was exporting Nicaraguan snook, dried shrimp, and lobster to Limon, Costa Rica, using Bluefields and the Corn Islands as my bases of operation.

I got to know the Miskito Coast well, was glad I did it, but would not do it again.

Bad outboard motors, bad gasoline, and sudden squalls in the Caribbean almost drowned me a few times. And then there was the cocaine trade (called “white lobster” in this part of the world).

One time south of Bluefields by Silk Key, I came upon a boat, with blood on the gunwale and bullet holes in her sides. No one was in the boat. I did not like that one bit and I lost my enthusiasm for the sea.

Now it’s the mountains that draw me in rather than the sea, unlike most Americans here.

There was no 911 to call out by Silk Key like there’s no 911 to call here if you get into a bad situation now. That’s something expats need to think about.

I mention these activities as they were risky but manageable. I could estimate the risk, avoid being stupid, and got paid well for my work.

This time it’s different. We never saw it coming, and so the question is what to do now?

I sent my wife to the States for the time being, and I stay at our home, which I built myself. Its walls are solid quarry rock, four inches think.

All our stuff is here, along with many orchids, fifty teak trees, my library I’ve worked thirty years to accumulate, my saddles and horse tack, a few antiques, and fruit trees of various types, now giving me plenty of avocados and star fruits.

It’s much less expensive here than in either Costa Rica or Honduras and until recent events, much less violent.

The healthcare here is great. The detonating issue of the present violence, an increase in charges for Nicaraguan Social Security (the INSS), costs me $35 per month. That covers everything.

The local INSS hospital is one kilometer from my home and gives me all consultations, medicines, and medical services. Few Americans use the INSS. In my group of 800 retirees, I am the only American. Most Americans are not legal residents or come as retirees and thus excluded from INSS by their pensionado status.

Big mistake. If expats would study up on things before they come here, many would be eligible for INSS.

All the nurses and docs treat me like a favorite pet. They like my Gringo accent.

My wife and I are in good health, touch wood. We both have twinges of arthritis, but most people do when they hit seventy.

So what to do in times of insurrection?

First, keep your head about you. Yesterday I posted on Facebook:

¨At this point, the only thing I am going to post is that I suggest everyone call close family/ acquaintances/ friends, at least twice daily, here and in the foreign country of origin, to let family and them all know you are fine. I am talking to my children and wife twice daily and close friends. Not long blathering, not exaggerated rumors, but just that I am fine and maybe a few hard facts. We all hope there will be a solution. And do not do anything stupid like go to where you do not have to go, and sit things out, and stay off the sauce. Keep your head and do not make a mistake. ¨

Also, have a Plan B and the means to execute it.

Both our vehicles have enough fuel to make it to the Costa Rican border but I doubt I’ll do that. I have enough food for two weeks, and the maid will stay with me at least until my wife returns from the States.

Nicaraguan food isn’t all just gallo pinto and Tip Top. Expat writer Pat Werner talks about his favorite delicacies. Have you tried mondongo, rondon, or vaho? Where’s your favorite restaurant?https://t.co/cyonO4jXI8#Nicaragua #CentralAmerica #Food pic.twitter.com/YHbFa1cFki

— CentralAmericaLiving (@VidaAmerica) March 9, 2018

I am cooking my favorite foods, baked beans, and crock pot mondongo. This week we will cook crock pot boiled beef tongue in sweet tomato sauce, a Nicaraguan delicacy, along with too much guacamole.

And I’m working on a manuscript of American higher education in post-revolutionary Nicaragua.

Recent events are causing me to rewrite some chapters.

One problem is almost no American was here during the war and so has no real reference on how fast things can get dicey or change for the worse.

Particularly if they do not speak street Spanish and take advice from people with their own agendas.

It’s not a good idea to maintain an American higher education institution when it does not have a solid economic base.

Neither is a complete rejection of teaching Nicaraguan history, government, and institutions, so no one knows how we got to this place, and how to fix it.

How Nicaragua’s Protests Could Spread Elsewhere in Central America https://t.co/KpAz7QY7S0 via @Stratfor Worldview

— CentralAmericaLiving (@VidaAmerica) May 17, 2018

Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdés, at the onset of the Spanish conquest almost 500 years ago, wrote that Nicaragua was a paradise, with the most attractive inhabitants, and the best food.

It still is, but it keeps getting political hiccups, which can cause indigestion.

I hope things will resolve themselves, I can keep living here in Diriamba, and my wife will soon come back home.

I am going to sit here in my study and find out.

Related:

- The Nicaragua Protests: A Central American “Arab Spring”?

- Nicaragua Update: Is Nicaragua Safe To Visit Right Now?

Pat Werner is a longtime resident of Nicaragua, arriving in 1987. He lives outside of Diriamba, Nicaragua with his wife Chilo. More of his work can be found on his Nicaraguan Pathways website.