Costa Rica is a multicultural society with many foreigners living in it. And yet there often appears to be a gulf between Costa Ricans and foreign residents. Immigration attorney Rafael Valverde believes the fault lies with both sides and multiculturalism in Costa Rica is a positive thing. In this article he attempts to explain our differences and what we should do to bridge them.

I often wonder if Ticos and foreigners living in Costa Rica understand each other. I’m inclined to believe they don’t.

Both groups view each other through the prism of their idiosyncrasies and stereotypes.

Foreigners rationalize Tico behavior and culture through past experiences, through the customs of their home country, and with a sense they “know better”.

But Ticos are so obsessed with their nationality, they don’t accept the reality of their multiculturalism and face it with resistance.

It interests me how foreigners living in Costa Rica use the word “expat”.

The term refers to ostracizing one’s self from the homeland. But most foreigners don’t do that at all. In fact, they seem to get more attached to their homelands the longer they stay. I often see foreigners in Costa Rica attached to their customs and cultures without integrating into the country they’ve moved to.

Many expats cannot, will not, or do not learn Spanish. I know people who have lived in Costa Rica for decades and still can’t speak basic Spanish.

This inability comes from two factors. First, the lack of integration with Costa Ricans and second, the tendency to socialize only with other expats. I might also add in laziness as a third factor but as I’m feeling kind, I won’t.

But ask yourself how well do you really integrate. Do you make friends with Ticos, attend Tico events, or care about Tico culture? What is a güipipía? Who was Carmen Lyra? Have you read “Mamita Yunai” or “Cocorí“?

Not being willing or able to absorb the host culture inhibits you from detaching from your own. This also has the effect of limiting the ability to understand the host culture. It’s hard to embrace a culture if you’re not willing to uproot yourself from your own.

Expats love to criticize Costa Rica and its quirks.

That’s fine. Speaking as a Tico, there’s nothing wrong with that. I am the first to criticize my country, as there are so many opportunities lost here.

But foreigners base their criticism of Costa Rica on comparisons with their home countries. Like their home country was perfect in the first place.

Everybody lives in the boiling water of Friedrich Goltz. Sometimes, when you are swimming in it, you can’t see what’s wrong with your environment. The countries you come from are not perfect, but you’re so used to them, you don’t see their problems. But then you come to Costa Rica and it’s easy to see the deficiencies because you are not used to them when you arrive.

The important part about noticing the deficiencies here is to do something about them.

If you don’t like it, change it. Don’t complain, do something. If you don’t want to do anything, then don’t complain.

This goes back to lack of integration. It shows expats aren’t willing to integrate or take part in community activism.

Community action is a fundamental part of democracy. Costa Rica is a democracy and allows community organizations to take part in guaranteeing equal access to enforce certain rights.

But what I see is, instead of joining community organizations, expats detach themselves. They stick together and make their own organizations.

The problem is by doing this you’re not being part of the community you live in. Ticos interpret this message as expats saying “we know better than you”.

Ticos have a hard time embracing foreigners.

This is odd as Costa Rica is a country of immigrants. Costa Rica has never acknowledged the multinational nature of Tico culture.

Efforts over recent years to acknowledge indigenous groups and Costa Rica’s Afro-Caribbean communities have not included other groups who have immigrated here over the last century. That includes people from your country who call themselves “expats” and people from other countries – like Nicaragua – who call themselves immigrants.

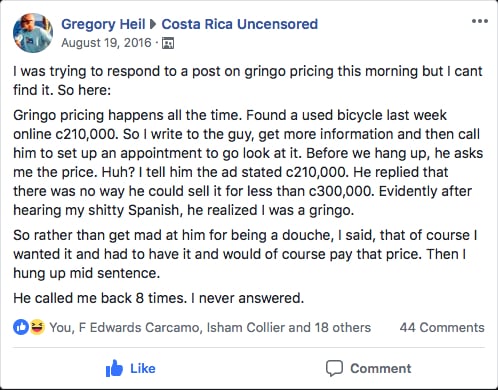

Everyone knows about the gringo prices in Costa Rica.

It happens all the time. Whether you’re buying a shirt, a car, a home, or a meal, discrimination against foreigners in the form of increased prices is common. We call it the blue-eyed tax. As soon as the service provider realizes you’re foreign, boom! They charge you extra.

This practice goes all the way to the top. Go to a national park and if you’re a foreigner without residency, you’ll pay more than a Costa Rican. In my book, this is discrimination, and we should accept no form of discrimination.

Costa Ricans feel entitled to charge more to foreigners. This has to stop.

Another issue is the whole “happiest country in the world thing”.

Each year, the Happy Planet Index ranks Costa Rica as one of the world’s happiest countries and I think this limits us. We think we’re already perfect and need not improve.

Did the creators of this index talk to the thousands of people waiting in line for surgery at a CAJA hospital? Or interview the tens of thousands of crime victims whose perpetrators did not go to jail? Did they speak to the 20% of the population who live in poverty or the almost 10% unemployed?

This fallacy prevents Ticos from seeing the inequalities and the realities of Costa Rica, one of them being we’re not so great.

So many issues need correcting and there’s plenty we can do to make this place better. Like recognizing the value of immigration and foreigners in Costa Rica.

Along with maintaining this is the happiest country in the world, Ticos also believe anything Costa Rican is perfect.

This nationalism is so profound, that again, it doesn’t allow us to see what’s wrong. La Sele made it to quarterfinals in the 2014 World Cup and Keylor Navas plays for Real Madrid. What else can you ask for?

Costa Ricans are so ethnocentric, all they care for are Ticos. They don’t realize how globalized this country is.

Ticos are proud that Intel is here (whatever remains of it) and it upset them when they closed the manufacturing plant.

Coffee, which is not an endemic crop, built Costa Rica, and we have been exporting it for almost two hundred years. Yet Ticos love to go to Starbucks. That is the epitome of globalization, but we don’t view it that way. We went nuts when they opened PF Chang’s, a “Chinese” food chain from the US.

The point is Costa Rica already has so much foreign influence.

The two best Olympic swimmers in the history of Costa Rica are Nicaraguan/German immigrants. Franklin Chang is a descendant of Chinese immigrants. The founder of Cafe Britt is from the US and the founders of the national park system were Swedish and Danish.

What I’m saying is that Costa Rica is a multicultural country but we are missing the opportunity to embrace that multiculturalism.

Both Ticos and foreigners need to get out of their comfort zones and get to understand each other more.

I know people will call me negative but I prefer not to believe Costa Rica is perfect. I prefer to recognize our weaknesses as a nation and work on eradicating those weaknesses.

I want to stir up a discussion so we can come up with better ideas for integration.

A longer version of this article originally appeared on the Outlier Legal blog. It has been summarized here with the permission of the author.

Rafael Valverde is a social commentator, critic, lawyer, and advocate for immigrant/expat rights in Costa Rica. He lives with his wife, Dawn, in Escazu, Costa Rica.